Set against a backdrop of luscious green flora and the deep blue sea beyond every hillside, Pantelleria’s well established wine tradition is indeed a beautifully picturesque and colourful scene. Long, sunny days freshened by relentless winds provide the perfect conditions for drying grapes, a practice introduced centuries ago by Arab settlers, and one that today represents the essence of Pantelleria’s reputation for producing luxuriously sweet ‘passito’ wines.

The process of making sweet wines from dried grapes is a well understood concept in the world of Italian wine, but few people are overtly familiar with Pantelleria - its geography or its wines. Nevertheless the island is a magical place, full of exotic landscapes, romantic stories, vivid characters and of course, a viticultural potential that deserves to occupy a higher plane in our wine consciousness.

Pantelleria is Sicily’s western-most outcrop of territory, closer in fact to the Tunisian mainland, and as such, enjoys a culturally diverse history in line with its North African proximity. Indeed, it is at times a demanding, almost inhospitable place to live. Battered incessantly by strong gales and chronically short of water, the island was once used as a penal colony by the Spanish, evidence perhaps of the latent environmental antagonism residing here. At their best though, the wines of Pantelleria are stunning, artisan creations by producers that have understood how to harness this territory’s unique climatic conditions and strong cultural traditions.

Beyond the mineral rich volcanic terrain the most defining factor of the island’s identity is the relentless winds that besiege and hound its shores. The Scirocco blows hard from the south, while the Mistral also crashes in from the north. Revealingly, Pantelleria is an Italian iteration of the Arabic bent-el rhia, meaning ‘daughter of the wind’. To combat the year long gusts, vines are planted as bush vines known as alberelli, half buried in the ground for shelter. Often that’s still not enough; makeshift windbreakers are used around flowering time to protect yields. Needless to say, the consequences of this method ensure labour is entirely manual.

Water is troublingly scarce, irrigation impossible. Vineyards are frequently enclosed within dry lava stone walls to help capture the moisture from the morning dew. Each civilisation has experienced the hardships of obtaining water here, but testament to the difficulties faced is the five-thousand year old technique known as the Pantellerian garden, or il giardino pantesco. A circular or oval shaped enclosure is built around the plant, particularly citrus trees, to help protect them from the wind, regulate temperature and encourage humidity. These unusual structures are particular to Pantelleria and a distinctive part of the island’s patrimony.

These combined factors have encouraged locals to find ways of mitigating the difficulties. A lengthy period of Arab colonisation and settlement resulted in the introduction of an architecture brought from the hot dry regions of North Africa and the Middle East. On Pantelleria single storey stone buildings known as dammusi are built with domed roofs, allowing for the capture of rainwater run off. Assembled with chunks of black lava stone that are held together through skill and knowhow rather than cement, they cast a somewhat rustic demeanour as they cling to barren hillsides.

Despite their impressive techniques for manipulating the elements, debate still surrounds the origins of Pantelleria’s key grape variety. Moscato d’Alessandria, as it’s commonly known, is listed in the Italian registry of varieties as Zibibbo, inspired presumably by the arabic Zabib, meaning raisin. While some I spoke to on the island claim it arrived (as the name suggests) from Alexandria in Egypt, it’s more likely that Zibibbo - probably a natural crossing between Moscato Bianco and Axina de Tres Bias - is Sicilian or Greek in provenance. This ancient variety potentially predates the island’s Arabic influence therefore. Even so, such etymology hints at its eventual role.

Zibibbo’s potential to accumulate and concentrate sugars, combined with the island’s hot, dry and windy climate makes it a very suitable variety for raisining in the October sunshine. Its popularity as a table grape made it immensely popular right up until fairly recently. There was once six-thousand hectares of Zibibbo on the island, much of them used to produce table grapes and raisins for the panattone industry. Plantings started to fall as more commercial pressures struck and the demand shifted elsewhere in favour of seedless grapes. What remains is exploited for the production of Passito di Pantelleria, a centuries old tradition of sweet winemaking.

Blending is a key aspect of the passito convention. The first crop to ripen is left to dry out for about thirty days, a routine known as appassimento in Italian. Although these raisins, or uva passa, are then pressed they’re too dry to release a juice. Instead the process splits the skin’s berries and helps facilitate the extraction of colour, sugar, acids and aroma. Each wine is different, its style influenced by the exact ratio of uva passa to fresh must. For most, the art of passito making lies in balancing freshness with sweetness. Inevitably therefore, the blending concept extends to the land. Each parcel yields a different potential for freshness and consequently, brings its owns personality to the table.

It is through deeper inspection of these individual sites that we may return to the notion of terrior. It is right to question the relevance of the term in an industry dominated by sweet wine production, especially when much of the fruit is raisined beyond identification, but the fashionable demand for cool climate winemaking is providing unexplored opportunities for dry wine. In turn, this is leading to a greater exploration of the soils and the emerging realisation that Pantelleria boasts outstanding viticultural potential. Defining Pantelleria simply as volcanic may no longer be enough for the increasingly curious consumer. We know vines work their way deep into the ground to reach much needed moisture and nutrients, but how important is the difference between fine sand and the larger pomace stones? Does the age of the eruption matter?

Marco da Bartoli has been producing his dry ‘Pietranera’ Zibibbo on the island since 1989 and it is often held up as one of Southern Italy’s great white wines, never mind Pantelleria’s. There are more high quality examples though. Coste Ghirlanda, situated on island’s south facing plains, produces an outstanding dry expression of [Zibibbo](/grape/zibiantidote to a mouthful of the island’s lightly spicy Biancolilla olives.

At eighty-three square kilometres Pantelleria is pretty big. The pine forest covered Montagna Grande sits in the middle of the island, reaching 836 metres above sea level, but around fifty other lower peaks, volcanic cones called kuddie dot the landscape. These various hillsides provide the starting point for a journey into the terroir. Producers have long understood that the island’s southern slopes yield a more acidic crop and those that own (or have access to) vineyards in hamlets such as Khamma, Martingana and Scauri will find it easier to add freshness to the riper, more concentrated grapes grown on the sun-drenched northern terraces. The argument for delivering a consistent house style makes perfect sense here, and the process of blending allows for that, but, emulating the growing culture on Etna of expressing the characteristics of individual contradas may also be a smart move. On an island as picturesque and beautiful as this, the marketing is surely there to support such an approach.

Pantelleria’s wine scene is awash with personalities, veterans of the island’s backbreaking annual winemaking struggle. The Pantesco contadino is a product of his isolated, farming environment. The sharp landscape of fierce black cliffs has essentially hemmed inhabitants in, expediting a custom of farming before fishing. This insular, land focussed history has created characters that are fully embellished, exaggerated even through the local dialect, a sort of Maltese sounding Sicilian, or perhaps a Sicilian sounding Maltese.

From a renovated dammuso in Bukkuram, Fabrizio Basile vinified his first passito in 2006. With his intense, excited stare rarely faltering, he cuts an uncanny resemblance to the mad Irishman in Braveheart. By all accounts the wine was good, but the learning curve has continued and more than a decade on his wines are now pretty special. He’s not afraid to push the boundaries however and the passage of time has not quelled his determination to experiment. When it comes to passito, chestnut and acacia wood are the main markers of difference, as well as varying levels of uva passa, but it is in his crafting of dry wines that we get a sense of his propensity for wild speculation.

Tasting alongside the traditional and well mannered Benedetto Renda, CEO of the volume orientated Cantine Pellegrino in Marsala, and president of the rejuvenated consorzio, there are plenty of points of view. For Benedetto, Fabrizio’s quasi random experimentation is a world away from his operations on the Sicilian mainland. He’s clearly baffled, but a sense of bewilderment descends as we taste ‘Parallo 37’, his 2010 creation of dry Zibibbo. “First of all, we have to abandon the vineyard” Fabrizio declares, a rapturous smile surging through his face, “then we wait a few years - four should be enough. After that, everything goes in the tank.” The vines still produce fruit, but ripeness is radically uneven. In theory the result is a wine that shows the freshness and concentration associated with both under and overripe berries. He calls it ‘wild wine’.

It’s too much for Benedetto. Fingers interlocked across his chest, he leans back and looks to the ceiling for support. How does this fit into the consorzio’s quest for a coherent contemporary indentity? Fabrizio is completely in his element though. Slowly oxidising over the course of a decade, the wine, fermented dry, is putting up a great defence of its unconventional origins. The nose throws off its veil of orange rind and bitter marmalade to reveal something reminiscent of Olarosso sherry; its walnut aromas are lodged amongst dried fruit and padded in with toast and tobacco. As complexity builds - hints of autumn truffle and festive spice - Fabrizio grins, “I closed the barrel one day, and opened it up seven years later”. As he marches into his local trattoria for lunch, bantering and back slapping with fellow farmers and field hands, one gets the sense that Pantelleria is very much his island.

Salvatore Murana is widely known throughout the Italian wine trade. He’s undoubtedly one of the great ambassadors of Pantelleria, quietly dedicating himself to the respect of his territory and the production of his wines. Six generations of winemaking have imparted Salvatore with a sense of time however, and, his own insignificance within it. He’s philosophical. The winds blew here long before him and they’ll continue to blow after he’s gone. From his terrace he starts our conversation with a reflection on nature’s cycle, pointing at the nearby cemetery that sits between two kuddie. He’s interested in man’s relationship with the land and the importance of not losing our focus on the things that sustain us.

We set out on a stroll through his vineyards in Mueggen, his dammuso restaurant seemingly the only significant structure as far the eye can see. In total he owns seventeen hectares of vines in various parts of the island, but here, some of them look as old as time. It’s said that some parcels were planted with cordon spur and on purchasing the land Salvatore ruthlessly ripped them out, returning his domain to the traditional Pantellerian panorama.

Murana is in no rush. Pulling at the odd vine, he slips in and out anecdotes about the eternal symbiosis of man and nature. Benedetto lets out his familiar shake of the head, aware perhaps that such a pastiche of poetic fragments and meandering reflection is incompatible with the financial realities and fiscal duties of Pellegrino. He affords himself a few moments off however, and soon finds himself basking in the island’s long farming traditions, built on by one civilisation after another, and Salvatore’s rhythmic dialectic tangents. “Tranni i pisci du mari tutti veni da i tirrineni” - Everything except the fish comes from the land.

Over lunch Murana oozes with pride. His early morning gatherings have brought in an assortment of vegetables and nuts, all of which find their way into an abundant picnic of antipasti, washed down with four vintages of his dry Bianco di Pantelleria drawn straight from the tanks. Showing a note of fresh lemon, they are crisp, and delicious. We start with 2018, but on reaching the ’16 he leans in and beckons me to listen. “Now we’re starting to get a serious wine”. I want to take notes, make my usual list of fruits, but he’s unimpressed. Wine should be a moment of shared pleasure, a moment of mutual understanding. Work and lunch should not mix.

The cellar is more like a craftsman’s workshop than a winery. There are nuts, bolts and stainless steel tanks everywhere. In the cellar I enquire into the amount of uva passa that might find its way into the blend. Murana’s intense stare doesn’t waver. “Imagine La Dolce Vita…” he pronounces, deadpan, as I brace myself for another profound island musing. “Would you ask Anita Ekberg her age”? Once again my attempts to fathom out the magic are thwarted. I push, keen to understand which vats contain which villagedoes, but the tremendous presence of sugar means these wines go on and on for years. There comes a point where there’s no point thinking about evolution and drinkability; instead marvelling at the complexity, concentration and longevity is an altogether more rewarding experience.

Eventually we reach one of the cellar’s oldest buckets. It’s 1976. Murana shrugs away descriptions of its taste. It’s given by the land, and must be respected; it’s a wine to be silent with, and meditate. “Tranni i pisci du mari tutti veni da i tirrineni”. As we sail through a back catalogue of vintages it becomes clear he’s got an awful lot of wine here. In recognition of the fact, there’s a perception these wines no longer belong to him, rather they represent Pantelleria’s viticultural heritage, Murana merely their custodian.

A tasting at Marco da Bartoli’s estate in Bukkuram proved to be yet another insightful exercise, reaffirming a realisation of just how good Pantelleria’s passito can be. I tasted two vintages of the flagship Vigna del Padre again noting its exceptional evolution, this time with the influence of wood. The 2014, just starting to find its feet, showed vibrant notes of orange rind and stone fruit. It was luxurious, viscous, polished, full of Christmas spice. The 2000 however, now almost twenty years old, delivered waves of caramel, toffee, liquid treacle, fruit cake and indulgent chocolate coated hazelnut. Not only was it a sublime wine, it still had plenty of life ahead of it.

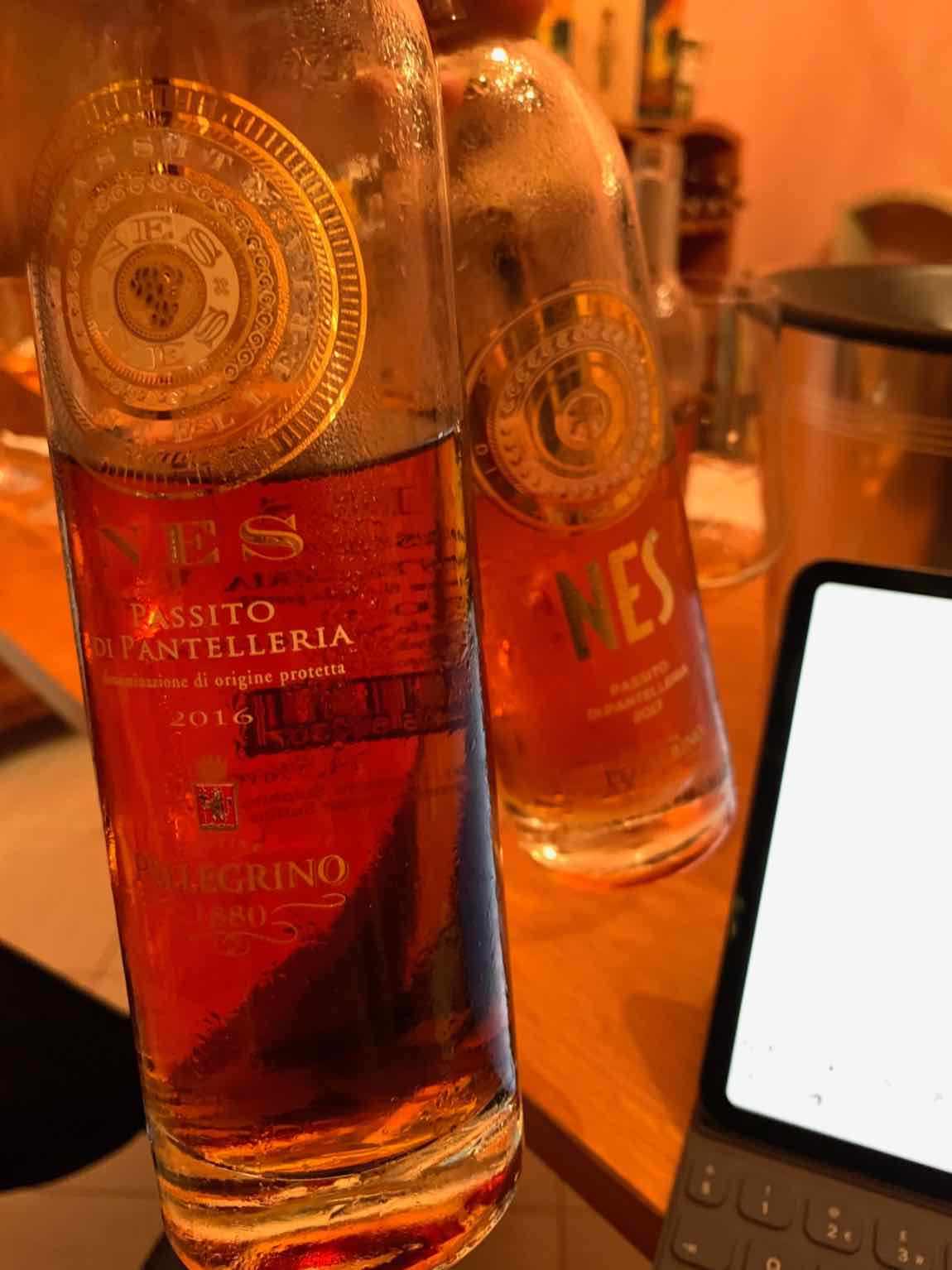

By the time we reached Pellegrino’s island base, it’s dark, and the winds have picked up to the point of inducing ear ache. The cellar, epitomised by its capacity to process a considerable influx of grapes, smacks of the 1970s, of an era before anyone considered the concept of enotourism. It’s stark, functional, and devoid of romance. Here though, the reality of local economics sets in. Through their purchase of fruit, Pellegrino control 75% of the island’s vineyards, mostly in the name of making Moscato di Pantelleria, a lighter, less complex version of passito. Although Pellegrino have their critics in the wine world, their operations here are slightly different. Production is fairly low and the natural growing conditions reduce the reliance on chemicals in the vineyard. Since Pellegrino are instrumental in the development of Pantelleria’s global reputation, it’s surely good news that NES, their modestly priced passito is a good wine and rarely surpasses 60,000 bottles a year.

Back in Khamma, at the Donnafugata estate, I’m shocked (and impressed) that production of Ben Ryé, the island’s most famous and expensive passito, is now up to 80,000 bottles a year. Of all the wines I tasted this stood out for both its explosive levels of exotic fruit, but also the harmony with which acidity merged with concentrated sweetness. Choice is clearly advantageous. Grapes are harvested from over a dozen contradas that in total span sixty-eight hectares. Fruit from Khamma, Martingana and Punta Karace tends to be picked in August and bunches are carefully laid out on racks to wither under the sun. The second harvest takes place in September but the philosophy here is to let the variety speak for itself meaning fermentation and maturation take place in stainless steel.

The 2017 packed a bold and strong nose of mature fruit. Orange rind and macerated apricots emerged while on the palate there was a prominent mineral, almost rocky note that lingered through an oily, treacle-like texture. Although 2016 was more subdued, 2014 boasted an intense nose made complex by notes of fresh tangerine, subtle whiffs of hazelnut and toast. Some caramelised character hit the palate but it showed the same deliciously long sweetness on the finish. I scribbled ‘the best so far’ in my journal.

Heading into more evolved territory the 2010 revealed a dark tawny colour tending towards brown; the nose was very interesting hinting at coffee and nutmeg. The palate combined flavours of bitter almond with raisin-packed fruit cakes. Interestingly though it was more evolved than the 2008, which was initially quite closed. With time it started to unfurl aromas of bruised peach and apricot, but was lifted by appley freshness.

Producers inevitably want to diversify their range with dry wines, and in a climate of falling sweet wine sales and the fervent interest in volcanic terroir, this is probably a sensible move. That being said, passito is still and should remain the key product. The history and traditions behind its production have contributed to Pantelleria’s recently awarded UNESCO world heritage site status, and with the right communication approach, there is no reason why producers shouldn’t seek to leverage this incredible charm. We’re living in an age that celebrates individuality, and where consumers seek authenticity. Pantelleria has everything going for it - the terroir is distinctive, the island’s viticultural provenance undeniable. Growers are full of passion and the wines, able to improve for decades, deserve a greater audience. My advice to wine lovers is put some away in the cellar; it’s only a matter of time before these volcanic treasures are discovered, for they live and breathe all the hallmarks of truly great wine.